X

The San Sebastian Festival has unveiled the image of its 63rd edition. The design of the official poster represents the stimulation of the senses prompted in spectators by cinema. The Festival will run from Friday, 18 until Saturday, 26 September.

The new image for the 63rd edition of the San Sebastian Festival was unveiled at an event in the Newton Auditorium of San Sebastian’s Eureka! Zientzia Museoa. An announcement was also made at the gathering as to the winning proposals of the poster competition called by the Festival for the Official, New Directors, Horizontes Latinos, Pearls, Zabaltegi and Culinary Zinema sections. Open to graphic designers around the world, this fourth edition saw the highest participation yet, with 1,726 proposals from 415 authors.

In the Official selection poster category, “El espectador” (The Spectator) by the graphic designer and illustrator from Uruguay, Matías Francolino, and the designer from Vitoria living in Uruguay, Blanka Barrio.

In the Official selection poster category, “El espectador” (The Spectator) by the graphic designer and illustrator from Uruguay, Matías Francolino, and the designer from Vitoria living in Uruguay, Blanka Barrio.

In the Horizontes Latinos category, “Mi horizonte” (My horizon), by the young designer from San Sebastian, Maite Rosende:

In the Horizontes Latinos category, “Mi horizonte” (My horizon), by the young designer from San Sebastian, Maite Rosende:

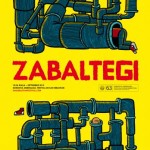

The poster “Tuberías 3” (Pipes 3) has been chosen as the image of this year’s Zabaltegi section. Its author is the Bolivian graphic artist Marco Tóxico. Marco has exhibited and published in several countries and was selected as one of the top ten 10 illustrators at Ukraine’s COW International Design Festival in 2012. In 2014 his poster was selected as the official image of the Montreal International Film Festival in Canada.

The poster “Tuberías 3” (Pipes 3) has been chosen as the image of this year’s Zabaltegi section. Its author is the Bolivian graphic artist Marco Tóxico. Marco has exhibited and published in several countries and was selected as one of the top ten 10 illustrators at Ukraine’s COW International Design Festival in 2012. In 2014 his poster was selected as the official image of the Montreal International Film Festival in Canada. Lastly, for the section dedicated to cinema and gastronomy: Culinary Zinema, the chosen poster is „Marilyn“ by the duo formed by Noemí Gómez Lobo from Asturias and Diego Martín Sánchez, from Salamanca, who have been working since 2012 on different projects that explore the hazy limits between art, architecture and design.

Lastly, for the section dedicated to cinema and gastronomy: Culinary Zinema, the chosen poster is „Marilyn“ by the duo formed by Noemí Gómez Lobo from Asturias and Diego Martín Sánchez, from Salamanca, who have been working since 2012 on different projects that explore the hazy limits between art, architecture and design.

The 63rd edition of the San Sebastian Festival will dedicate a cycle to new Japanese independent cinema!

New Japanese independent cinema 2000-2015 is the thematic retrospective programmed by the San Sebastian Festival for its 63rd edition, to take place from September 18-26.

Beyond the bounds of the films produced by the big studios, the phenomenon of independent cinema in Japan has generated an important source of cinematic creativity expressed in a series of films produced outside the industry. This category includes not only the first works by young directors, but also those by a series of long-standing filmmakers who find greater expressive freedom in this territory outside the clutches of commercial cinema.

The cycle therefore becomes an overview of Japanese independent production in the last 15 years, a showcase offering the opportunity to discover the vitality and energy of the film industry in that country thanks to the work of some of today’s most eye-catching filmmakers.

Among the titles making up the retrospective are works by outstanding figures in Japan’s contemporary film world: H Story (2001) by Nobuhiro Suwa, A Snake of June (Rokugatsu no hebi, 2002) by Shin’ya Tsukamoto, Bright Future (Akarui mirai, 2003) by Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Vibrator (2003) by Ryuichi Hiroki, Bashing (2005) by Masahiro Kobayashi, Birth/Mother (Tarachime, 2006) by Naomi Kawase and Love Exposure (Ai no mukidashi, 2008) by Shion Sono.

Alongside the above we will also present the works of several new talents to have made their debut since 2000: Hole in the Sky (Sora no ana, 2001) by Kazuyoshi Kumakiri, Border Line (2002) by Sang-il Lee,No One’s Ark (Baka no hakobune, 2003) by Nobuhiro Yamashita, The Soup, One Morning (Aru asa, soup wa, 2005) by Izumi Takahashi, Fourteen (Ju-yon-sai, 2007) by Hiromasa Hirosue, Sex Is Not Laughing Matter (Hito no sekkuso o warauna, 2007) by Nami Iguchi, Passion (2008) by Ryûsuke Hamaguchi,Parade (Parêdo, 2009) by Isao Yukisada, Yellow Kid (Ierô Kiddo, 2009) de Tetsuya Mariko, Love Addiction(Fuyu no kemono, 2010) by Nobuteru Uchida, No Man’s Zone (Mujin chitai, 2011) by Toshifumi Fujiwara,Saudade (Saudâji, 2011) by Katsuya Tomita, Cold Bloom (Sakura namiki no mankai no shita ni, 2012) by Atsushi Funahashi, The Cowards Who Looked To The Sky (Fugainai bokutachi wa sora o mita, 2012) by Yuki Tanada, Au revoir l’eté (Hotori no sakuko, 2013) by Kôji Fukada, The Tale of Iya (Iya monogatari: Oku no hito, 2013) by Tetsuichirô Tsuta and The Light Shines Only There (Soko nomi nite hikari kagayaku, 2014) by Mipo Oh.

The Japanese independent cinema 2000-2015 cycle is organised by the San Sebastian Festival in collaboration with CulturArts-IVAC (Valencia), the Filmoteca Vasca, San Telmo Museum and San Sebastian European Capital of Culture 2016.

The retrospective will be accompanied by the publication of a book coordinated by Shozo Ichiyama.

The 63rd edition of the San Sebastian Festival will dedicate a retrospective to the directors Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack!

Merian C. Cooper (1893-1973) and Ernest B. Schoedsack (1893-1979) were, in the golden age of North American movies, one of the strangest and most exciting creative twosomes ever to come out of Hollywood. This year’s edition of the San Sebastian Festival will recover their work in a cycle dedicated to their films as directors.

Acclaimed for generations as the masterminds of the iconic King Kong (1933), Cooper and Schoedsack’s contribution to fantasy cinema didn’t stop at this chef d’oeuvre remodelling the Beauty and the Beast myth, instead creating a delirious and antediluvian visual world taking its inspiration from Gustave Doré and innovating the stop motion animation technique. They also brought us other equally attractive proposals with titles such as The Most Dangerous Game (1932), the fabulous movie about man hunting man, produced by Cooper and directed by Schoedsack and Irving Pichel, and Dr. Cyclops (1940), a telluric fantasy about miniature beings helmed solo by Schoedsack.

Cooper was a fighter pilot in the First World War, a POW in a German camp, a member of a volunteer squadron during the subsequent conflict between Poland and the Soviet Union, and later again a colonel in the US Army Air Forces during World War II. Schoedsack too fought in the first battle, but as a member of the Signal Corps, the army information squad. He produced many works as a journalist and took his first steps in the movie industry as a cameraman at Mack Sennett’s Keystone Pictures. Both born adventurers, they participated in several anthropological expeditions as cameramen, hence their passion for documentary cinema.

They made their debut jointly directing two masterpieces in the genre, Grass (1925) and Chang (1927). In the former they portrayed the everyday lives of a nomad tribe in Persia (today’s Iran), while in the latter they focussed on the relationship between a native from the Siam jungle and a baby elephant. Although they later made fantasy, drama, adventure and whodunnit movies, their fictional films always smacked of strong throwback to their documentary apprenticeship: the tales of King Kong and Zaroff suggest contact with exotic unexplored worlds as bigger-than-life fantasy merges throughout their work with the realities of the jungles and mountains of Asia and Africa. Hence the enormously personal style that characterises their films. After their first two documentaries they made The Four Feathers (1929), the first talkie version of A.E.W. Masson’s famous book about honour and cowardice.

The Cooper-Schoedsack combo forged full steam ahead throughout the 30s, forming a team with the screenwriter Ruth Rose (1891-1978). Rose and Schoedsack had coincided on an expedition to the Galapagos Island and married in 1926. The three launched films in difference genres, produced by Cooper and helmed solo or in collaboration by Schoedsack: mystery films like The Monkey’s Paw (1933) and Blind Adventure (1933); adventure stories such as Trouble in Morocco (1937) and Outlaws of the Orient (1937); an adaptation of Bulwer-Lytton’s popular novel The Last Days of Pompeii (1935); and even comedy-dramas like Long Lost Father (1934), starring John Barrymore. Of their hugely successful King Kong, which would go decades later to generate remakes shot by John Guillermin and Peter Jackson, they too made delightful continuations and offshoots: Son of Kong (1933) and Mighty Joe Young (1949). The stop motion style used by Willis O’Brien in the first Kong was repeated in Mighty Joe Young by Ray Harryhausen, who went on to become one of the great masters of this artisan procedure.

Following the enormous challenge of King Kong, heyday of the 30’s fantasy genre and metaphor of the economic situation assailing the country after the Wall Street crash of 1929, Cooper gradually distanced himself from directing and took up position as one of the leading producers at RKO. As studio head, he would produce, among other films, the first of the elegant musical comedies for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Flying Down to Rio (1933), by Thornton Freeland, and the adventure fantasy She (1935), by Lansing C. Holden and Irving Pichel, according to the novel by H. Rider Haggard, of which a remake was made years later, produced by Hammer Film.

In 1933 he joined forces with David O. Selznick at Pioneer Pictures, a production company dedicated to experimenting with trichrome Technicolor: the first film launched by Pioneer using the technique was Becky Sharp (1935), by Rouben Mamoulian. Later, towards the end of the forties, he founded with John Ford the small independent company Argosy Pictures, with which they produced The Fugitive (1947),Fort Apache (1948), Rio Grande (1950), The Quiet Man (1952) and The Searchers (1956), among other movies by Ford. Cooper was also among the promotors of the Cinerama format, created by the photographer and moviemaker Fred Waller, in the early 50s.

The retrospective, dedicated to their work as directors in addition to those made solo by Schoedsack, is organised by the San Sebastian Festival in collaboration with the Filmoteca Española. The cycle will be accompanied by the publication of a book dedicated to the two filmmakers.

Films in Progress 28 opens its call for submissions 21, 22 and 23 September 2015!

Films in Progress, the twice-yearly event organised by the San Sebastian and Toulouse Festivals, is now receiving submissions for Films in Progress 28.

The initiative has the objective of contributing to the completion of Latin-American feature films faced with difficulties at the post-production stage and of promoting their international distribution. The films must have a running time of more than 60 minutes and must be totally or partially produced by production companies in Latin American countries.

Films in Progress has contributed to the completion and dissemination of remarkable Latin American productions. Films presented at the last three editions of Films in Progress, such as Gloria by Sebastián Lelio, Matar a un hombre by Alejandro Fernández Almendras, Historia del miedo by Benjamín Naishtat, Ixcanul by Jayro Bustamante and La Mujer de Barro by Sergio Castro have gone on to participate and garner awards at important international festivals such as Berlin, Rotterdam and Sundance.

Films in Progress 28 and the IV Europe-Latin America Co-Production Forum will run on the same dates, seeking to generate professional synergies, foster co-productions and the international circulation of films.

AWARDS

The Films in Progress Industry Award will be given at Films in Progress 28 by the companies Daniel Goldstein, Deluxe Spain, Dolby Iberia, Laserfilm Cine y Video, Nephilim Producciones, No problem Sonido, and Wanda Visión. The award consists of the post-production of a film until obtaining a DCP subtitled in English and its distribution in Spain.

As a new feature, 2015 sees creation of the Ibermedia TV Films in Progress Award, going to the winning film of the Films in Progress Industry Award. Granted by the Conference of Ibero-American Cinematographic Authorities (CACI) by means of the Ibermedia Programme, the award consists of including the film in the Grant Programme for Television Broadcast: authorisation of non-exclusive broadcasting on Ibermedia TV and Ibermedia Digital for the value of US$25,000 (full-length feature film) or US$15,000 (documentary).

X